The town that used literacy to tackle exclusions

While it’s a step too far to claim schools are excluding children for not being able to read, what is true is that children who struggle to read are being excluded at far higher rates than their classmates.

It’s well known that the most common reason for children being excluded is “persistent disruptive behaviour”, accounting for about a third of both permanent and fixed-term exclusions (expulsions and suspensions, respectively). What is less well documented, are the reasons why children might be disrupting lessons in the first place.

One hypothesis often mentioned by professionals, is that many children who are excluded appear to lack the language and communication skills required to access a secondary school curriculum.[1] (The vast majority of exclusions happen in secondary schools – ten times more frequently than in primary.) There is also a body of international research showing that behavioural problems often go hand-in-hand with low language proficiency.[2]

This is the story of how all the headteachers in one town came together to investigate this problem among their pupils, and what they found.

Brought together three years ago under Justine Greening’s Opportunity Area scheme, the headteachers of Blackpool’s eight secondary schools and the pupil referral unit put their heads together to investigate their suspicion that low literacy levels in the town could be linked to their high exclusion rates. Blackpool has the third highest rate in the country of children being moved into alternative provision.

Exclusions were more frequent in secondary school, so they decided to focus on years 7, 8 and 9. First, they needed accurate, comparable data, so in 2018, almost every key stage 3 pupil in the town completed the GL Assessment New Group Reading Test.

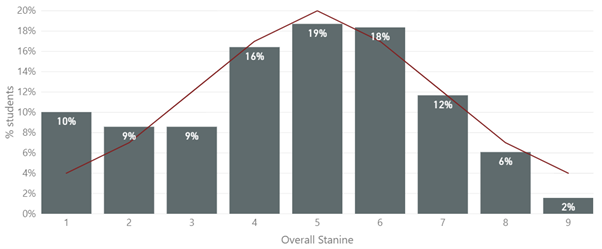

When the results were compared to national averages, the town’s education leaders were struck hard by the fact that across Blackpool, there were 2.5 times as many pupils in the lowest group compared to the national picture (see figure 1).

Figure 1

Reading comprehension levels of key stage 3 pupils across Blackpool, as measured on the GL Assessment New Group Reading Test, June-October 2018

Key: Red line is the national average score

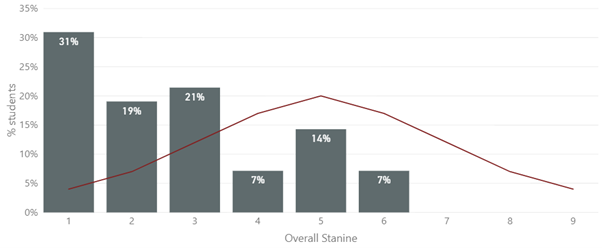

What was even more striking, however, were the literacy profiles of the children in the pupil referral unit. Half of their pupils were in the lowest two brackets for literacy for children of their age nationally – compared to the population average of one in ten (see figure 2).

Figure 2

Reading comprehension levels of key stage 3 pupils in alternative provision in Blackpool, as measured on the GL Assessment New Group Reading Test, June-October 2018

Key: Red line is the national average score

While they were not able to determine causation, the correlation was so striking that it confirmed the headteachers’ hunch that literacy was something they needed to address urgently and collectively, as a town.

The schools took a three-pronged approach, comprising professional development, literacy interventions, and reviews of existing provision.

They brought in high-quality professional development from the likes of Alex Quigley, EEF-Blackpool Research school, CUREE and the Teacher Development Trust.

They also implemented a range of universal, cohort-specific and targeted literacy interventions. Some implemented the EEF-endorsed Accelerated Reader programme, and others – mainly due to a lack of available books and computer access – developed their own Literacy Canon programme.

One year in, the project was already improving literacy levels across the town. However, Blackpool’s senior leaders felt there was much still to be done in order to unlock the potential of all the most vulnerable learners.

In response to this challenge schools undertook extensive reviews of their provision for children with reading ages far below their chronological age. As part of this process, they committed to share ‘what works’ and just as importantly, ‘what didn’t’ across their respective settings.

As a result of the locally-led research, all schools came to the conclusion that many of the challenges around reading and behaviour that they were seeing were potentially due to speech, language and communication needs (SLCN) that had previously gone unmet.

Tackling widespread low literacy and SLCN difficulties is highly complex and requires a long-term approach. Through the literacy project, which has been supported by Right to Succeed, Blackpool senior leaders have committed to: more effective screening of need; additional pupil reading time; releasing SENCOs to conduct research and undertake nationally-recognised professional development in SLCN, and; working alongside the council’s SEND and inclusion team to develop a sustainable approach for the children of Blackpool moving forward.

This is just one example of

what can happen when local leaders get curious about the reasons behind

persistent disruptive behaviour, and work collectively to find a solution.

[1] When the government commissioned a recent report into alternative provision, a “strong theme” heard by researchers was of pupils who had been diagnosed with social, emotional and mental health needs, “when further assessment revealed that pupil’s behaviour was the result of underlying and unmet communication and interaction or learning needs”. Alternative provision market analysis, Oct 2018, Isos Partnership, published by the Department for Education, p.51

[2] Benner, G. J., Nelson, J. R., & Epstein, M. H. (2002). Language skills of children with EBD: A literature review. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 10(1), 43-59.

Hollo A., Wehby J. & Oliver R. M. (2014). Unidentified Language Deficits in Children with Emotional and Behavioral Disorders: A Meta-Analysis. Exceptional Children